Artificial Intelligence (AI) is no longer just a buzzword. It is embedded in everyday work, from drafting emails to automating entire workflows. For Memeburn’s…

Here’s how SA startups can legally create an offshore company

If you’re a South African setting up an offshore company needn’t be a headache.

In this, my second article on how to build international business structures (see the first here), I will explain what your international company structure looks like, from an SA perspective.

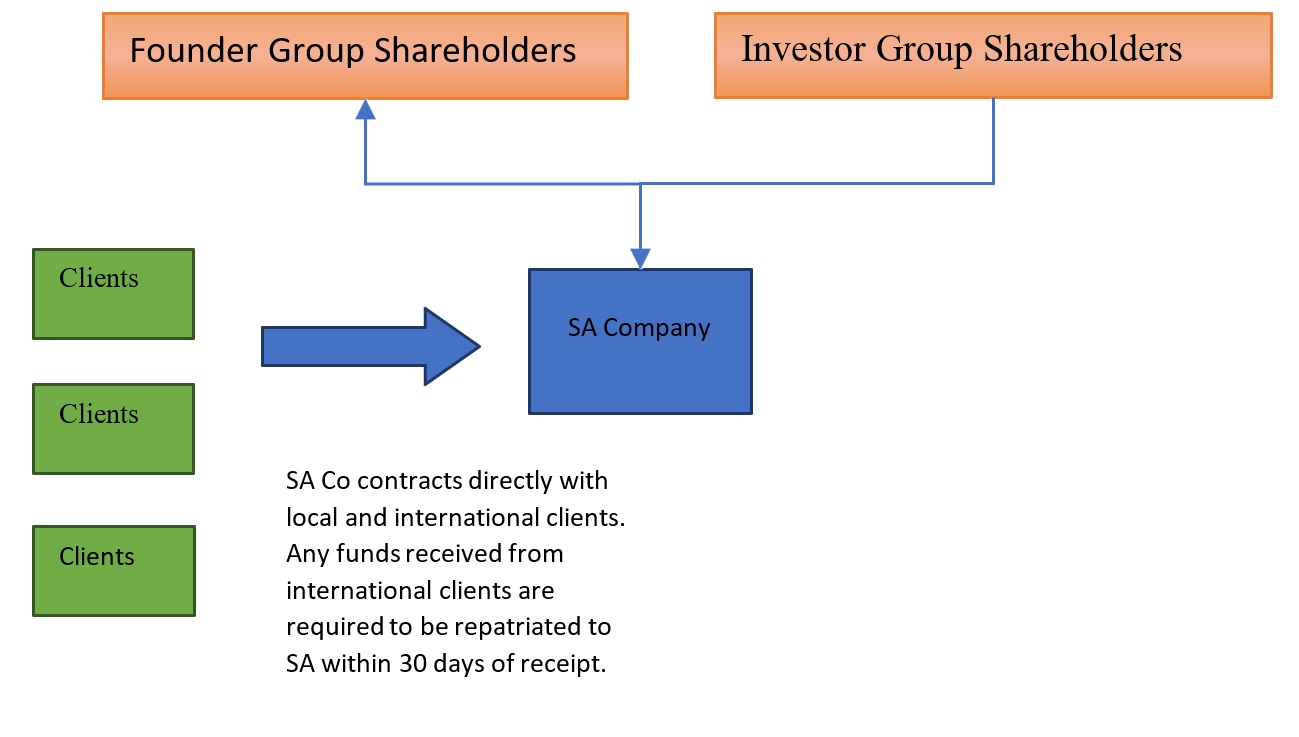

An international group owned by South Africans will look different to a SA company based in South Africa. This is because South African’s have specific restrictions placed on them by exchange control.

This article explains why the structure will look different, and how it can achieve the desired end result anyway.

As a starting point, here is the typical startup company:

Offshore firm can’t own SA company

If you (the shareholders) are South African, then the offshore company (Offshore Co) can’t own the SA company (SA Co).

This important point needs to be understood for its disorderly effect on international structures. It means that SA shareholders typically can’t create an offshore holding company which owns their SA subsidiary companies.

One more time, with feeling. Offshore Co can’t be the holding company of SA Co. This is probably the most infuriating law in our otherwise amazing country.

An international group owned by South Africans will look different to that of a local firm, because of exchange control restrictions

To avoid causing anguish, I will explain the reasons for this structural peculiarity in a coming article, which you can read after taking a good dose of anger management medication.

For the moment and for completeness, exceptions exist (a) for employee share incentive schemes, (b) where less than 40% of the Offshore Co is owned by SA companies (not individuals) and (c) in the case of technology companies setting up subsidiaries offshore for fund raising purposes.

Assuming that these exceptions don’t apply, the solution to this problem is to avoid dealing with it (in this case however, even Sigmund Freud would not disapprove).

A simple solution

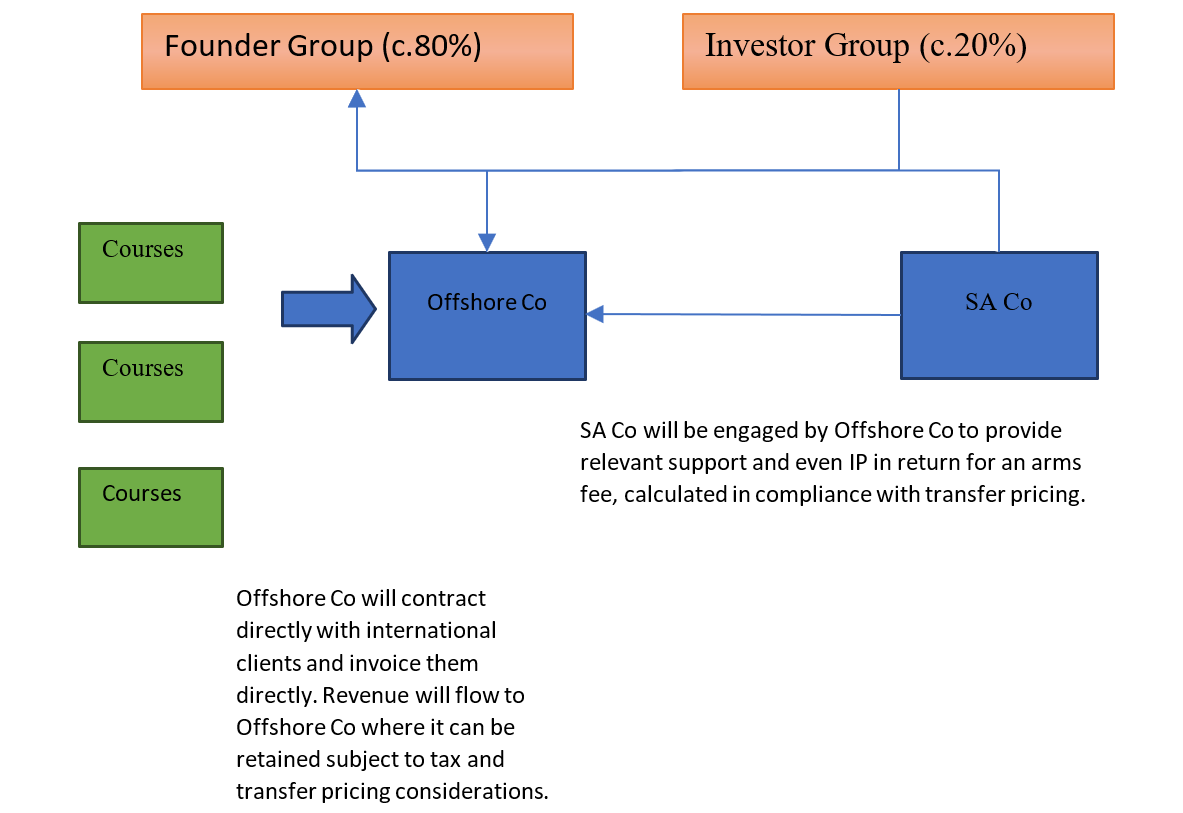

The answer is a cumbersome, but simple one — all the shareholders will have to acquire a brand new, offshore company, and then each shareholder holds shares directly in that Offshore Co.

The result is that you will have two parallel companies — the SA company (covering all SA functions), and the Offshore Co (which covers the entire market outside of South Africa).

Each of these companies will be directly owned by all the shareholders in exactly the same proportionate shareholding (see the below example).

This is perfectly legal because there is no restriction on SA individual residents acquiring shares in offshore companies (as long as the offshore companies don’t own SA companies).

Exchange control allowances

Strictly speaking, I should mention here that each SA shareholder must use their exchange control allowance to fund their purchase of shares in Offshore Co.

The allowance is an annual discretionary amount of R1-million, and a further R10-million with a tax clearance – and as Offshore Co will likely be a shell, it will probably cost a nominal amount to set up.

The next step is to contractually bond the shares of the two companies — meaning that the shares in each of the companies cannot be separately traded.

This is intended to create a single point of exit or entry for future investors into the group, and therefore synthetically mimicking a conventional “group” holding structure.

This solution is really very simple in concept. It effectively carves out the international operations of your business and places those operations into a corporate vehicle which can be entirely separate from SA tax, exchange controls and political or economic risk — if structured, operated and managed correctly.

That in itself can be a significant qualification, but more on that in the next article.

Read more: The ins and outs of taking your startup offshore

Adrian Dommisse has extensive experience in corporate and financial transactions across Africa, Europe, Eastern Europe, and the Middle East. He founded Dommisse Attorneys law firm in 2008, and holds three degrees in economics and law.

Featured image: Pexels via Pixabay